News

Edwards v Meril confirms UPC’s jurisdiction over acts of infringement before the court came into force

November 2024

In Edwards v Meril (UPC_CGI_15/2023), the UPC’s Munich local division refused to stay infringement proceedings pending an appeal on the central division’s finding of validity of the patent in amended form. In finding infringement in favour of Edwards, the local division paid significant attention to expert evidence when interpreting the claims and, unusually, also referred to definitions provided in one of the defendant’s own patents to confirm their interpretation. Furthermore, by taking a functional interpretation of the claims, the local division found infringement without having to consider Edward’s allegations of infringement under the doctrine of equivalents. The local division also paid short shrift to Meril’s suggestion that the UPC had no jurisdiction over acts of infringement committed before 1 June 2023 when the Agreement on the UPC came into force.

Background

This case concerned Edward’s successful infringement suit against Meril under EP 3 646 825 B1. Although Meril counterclaimed for revocation before the UPC’s Munich division, Meril also filed a separate action revocation at the central division. The case was bifurcated, with revocation and counterclaims for revocation consolidated and heard by the central division, which upheld the patent in amended form. The central division’s decision is now under appeal. Meril requested a stay of the infringement proceedings on the grounds that the central division had not considered all matters put before it. However, the local division found that Meril failed to demonstrate that the central division’s decision was manifestly and prima facie erroneous. As a result, no stay was granted.

Technical details

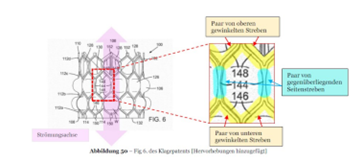

The patent concerned a prosthetic heart valve comprising a frame made up entirely of hexagonal cells. In their submissions, Edwards referred to the illustration below, which shows the hexagonal cells as well as opposing side struts (144) extending parallel to the flow axis of the valve.

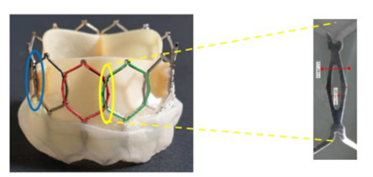

Meril contested that their valve was composed of octagonal cells marked in red and green in the below that partially overlap to form rhombic cells in the overlapping zone (see region in yellow).

Edward’s position was that there was infringement by the doctrine of equivalents. Meril’s position was that, contrary to the requirements of Edward’s claims, their valve was not made up entirely of hexagonal cells and was devoid side struts extending parallel to the flow axis of the valve.

Claim interpretation

Unsurprisingly, the case turned on the interpretation of the terms “strut,” “parallel,” and “(hexagonal) cell.”

In relation to the term “strut,” the court interpreted this term functionally, noting that the patent itself attributed different functions to the angled and vertical side struts of the frame. While the angled struts played a part in the compression of the valve, the vertical side struts were rigid during the collapse of the valve. The court held that this interpretation was consistent with the expert evidence provided by Meril.

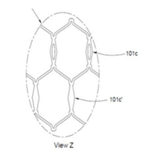

Perhaps more interestingly, the court also referred to Meril’s Indian patent application 202121947196 (IN’196) that was filed on 18 October 2021. Meril submitted this document as part of their defence. However, the court referred to the document when interpreting the term “strut,” noting that the side “struts” 101c and 101c’ illustrated in IN’196 behaved in substantially the same way despite the fact that 101c defined an open space, while 101c’ did not.

Some readers may be surprised by the court’s reference to a post-filed document for claim interpretation. However, it is safe to say that this document did not alter the conclusion that the court had already reached on the basis of interpreting the claim in the light of the description.

With regards to the term “parallel”, the court concluded that this “must not be understood in a strictly mathematical sense,” as the drawings in the description of the patent showed struts of a slight concave shape.

As regards the “(hexagonal) cell,” the court noted that the claim referred to a frame made up entirely of hexagonal cells. However, applying a functional interpretation to the term, the court noted that the frame was collapsible and expandable, implying that the cells had also to be collapsible and expandable since the frame was made up entirely of hexagonal cells. In this way, the court adopted an interpretation that allowed the claim to cover frames with non-hexagonal holes, provided that such holes were not collapsible and expandable. This interpretation ruled out Meril’s defence that their frame included rhombic cells, since the rhombic holes of Meril’s device did not collapse during compression of the valve and could, therefore, not be considered as “cells”. Together with the court’s interpretation of “strut” and “parallel”, this interpretation also put paid to Meril’s defence that their cells had an octagonal shape.

Conclusion

This case highlights how the court interpreted the claims functionally in the light of the description to provide the claim with a broader interpretation that perhaps might have been expected from the wording of the claims alone. Some practitioners may also be surprised by the court’s reliance on a prior patent application in confirming the interpretation of one of the patent terms.

The claim interpretation taken by the court meant that Meril was found to infringe. This made a consideration of Edward’s allegation of infringement by equivalents unnecessary. As a result of their finding of infringement, the court ordered Meril to provide Edwards with information on infringing acts committed since 17 March 2021, paying short shrift to Meril’s suggestion that the UPC had no jurisdiction over acts of infringement committed before 1 June 2023 when the Agreement on the UPC came into force.

This article was prepared by Partner & Patent Attorney Hsu Min Chung.